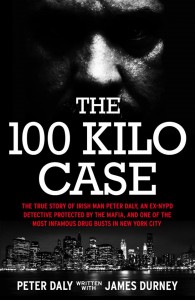

The 100 Kilo Case, the journey

James Durney

In the very early 1970s when I was a very young teenager, way below the legal age, I sneaked a book from my father’s pile of read, or to be read, books, writes Kildare writer James Durney, author of The 100 Kilo Case. That book was The Godfather by Mario Puzo. From the moment I delved into the world of American organised crime I was hooked.

There were two Irish characters in the book — Tom Hagen, Don Corleone’s adopted son, the family lawyer and consigliere (counselor); and Captain Mark McCluskey, a corrupt NYPD police captain. From then on, when reading books on organised crime like The Valachi Papers and My Life in the Mafia I was on the look-out for Irish characters and I discovered there was no shortage of them — good guys and bad guys.

I was torn between the two — the bad guys were tough, loyal, and had honour, but the good guys — the cops, special agents and investigators — were also honourable men. Mobsters could be admired, but I didn’t want to be one. I would rather be a cop like Eddie Egan in The French Connection, a rough detective who routinely broke the rules in his effort to nail criminals.

Growing up in a small town in Ireland I would dream of a life in New York City as a reporter or a patrolman, or detective. My mother had an uncle, who had run off to New York and made good and would claim me out, so all I needed was the fare. But in a cash-strapped Ireland of the mid-1970s this was not easy.

Like many kids of my generation I had a part-time job and from my meagre wages I established a flight-fund. A cut-out map of NYC also took pride of place on my wall, but only for a short time until other distractions — music, girls and alcohol — entered my head. The flight fund soon became an LP record fund and all dreams of New York were abandoned.

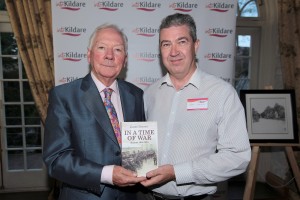

My reading continued, however, and I became something of an expert on the American Mob. Twenty-odd years later my first book The Mob. The history of Irish gangsters in America hit the shelves, but it was while working on another book The far side of the world. Irish servicemen in the Korean War 1950-53 that I met Peter Daly.

I interviewed Peter, an ex-US Army serviceman, for that publication. He had been in South Korea not long after the war ended on occupation duties and his story featured in the epilogue. However, Peter revealed he had led a more interesting life when he returned to New York as a patrolman and later as a detective with the Special Investigating Unit.

As a young cop he did a favour for Red Levine, an old hitman for the Mob’s enforcement arm, Murder Incorporated. Peter Maas had written about Red Levine in his best-selling book The Valachi Papers, so I knew Red was the guy who killed Salvatore Maranzano, the Mafia’s ‘boss of bosses’. In Carlito’s Way Carlito Brigante had said a ‘favour can kill you quicker than a bullet,’ but it seemed Peter had survived in jail because of his favours, or rather who he had done favours for.

Peter Maas’s biggest success was the book Serpico, the story of undercover cop Frank Serpico who was shot and badly injured in a drug bust in Brooklyn in 1971. It looked like Serpico had been set up by his police comrades because of his stance on corruption. I had read Serpico, empathised with his lonely fight against corruption in the NYPD. Peter Daly knew Frank Serpico — they had both served at the same time; Peter also knew Jimmy ‘the Gent’ Burke, Henry Hill, Tommy DeSimone and Paulie Vario from Goodfellas fame. He had done a favour for Jimmy Burke, too, while in Lewisburg Penitentiary. He also did favours for Henry Hill and lots of other mob guys. It’s how he survived.

I had read another cop book, Robert Daley’s Prince of the City. The 100 kilo case featured heavily in the book, but that was before I knew Peter Daly and the connection to one of the NYPD’s biggest drug seizures. After writing a dozen books on Irish and local history I was now back with my first love — organised crime.

Hollywood loves the crooked cop scenario — a down on his luck cop working for the Mob; cops ripping off drug dealers and dealing drugs, even doing hits. But that’s movie fiction, or is it? Peter Daly’s story was an eye-opener into a shady world of police corruption that seems to belong in the movies, but in reality was more the norm. The Knapp Commission, which investigated police corruption in the 1970s, divided corrupt officers into two types: meat-eaters, who ‘aggressively misuse their police powers for personal gain’, and grass-eaters, who ‘simply accept the payoffs that the happenstances of police work throw their way’.

Was Peter Daly a meat-eater or a grass-eater? Read The 100 Kilo Case and decide.